Having written the Frongoch trilogy (‘Turn of the Wheel’, ‘A Time of Goodbyes’ and to follow – ‘A Light in the Darkness’), it does feel sad in some ways to think that the mine no longer stands as it did in its glorious years. Not that I wish for tons of spoil, toxic with base metals to still be sprawled untidily in the valley. The remnants of the buildings that remain do however, only hint at the scale of operation that affected the lives and livelihoods of thousands of people in the valley. Miners, mine workers, their families and the businesses that sold products. Cart owners, chapels and even the schoolmaster and Doctor. All would have been impacted, and yet what is left as a testament to their lives is merely a shell. There are few photographs of it in operation, taken around 1901.

However, about 5-10 years ago, an animation was made of the history of the hydro electric station at Pont Ceunant. This was the first hydro in the area, installed in 1899 (to metric dimensions), to power the Frongoch mine, as its new Belgian owners sought to modernise the operation. This also included a large dressing mill, linked by tramway from the new winding gear of Vaughan’s shaft and pitheads with winding wheels. The animation by the company, Take 27, is 7 minutes long. It recreates the power station and explains all about it. It is superb and well worth a look, via this link Pont Ceunant, Aberystwyth. A Victorian Power Station for a Welsh Metal Mine – YouTube

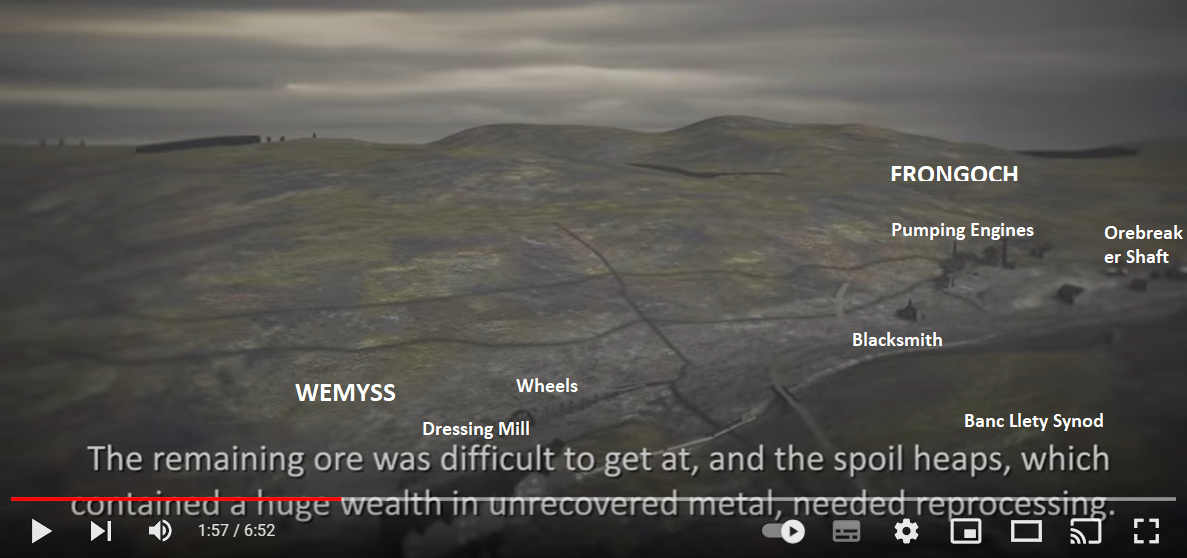

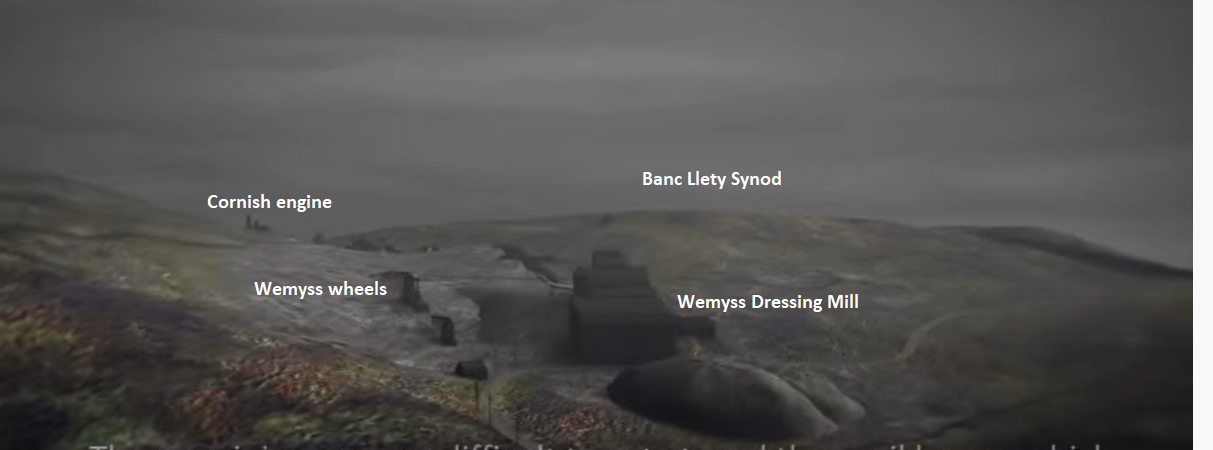

Commissioned by the RCAMHW and the Welsh Mines Preservation Trust, the animation pans down the valley and over the brow of the hill to the mine. Thus the old buildings are recreated for us to see how things were set up, which complements the maps provided in the novels. The images do not indicate, what is what, so I have taken some screen shots and added these. Many thanks to Ioan Lord of the WMPT for giving me permission to do so.

These images below, I hope, help illustrate the mine set up and provide another tool to help people understand the lie of the land I describe. The animation was breathtaking in its accuracy, as anyone who know the area would testify:

On this image, we are looking above Banc Llety Synod, to the North. Frongoch mine is to the right and the Wemyss mine to the left. the modern road to Trisant splits the two, being bridged over the tramway.

From below Wemyss mine, we look up towards Banc Llety Synod. The Dressing mill was built in 1899 and substantial stone work still remains in situ, cut into by the modern road below, as it heads up the valley from Trawscoed. The Frongoch mine was over the brow to the left of the water wheels, The Cornish engine’s chimney stack would be visible from this view. The road to the right of Banc Llety Synod carries on to New Row and then down to Pontrhydygroes.

This is further down the valley towards Trawscoed. Looking back, the small Red Rock (Graig Goch) mine is to the right, Pont Ceunant Hydro station to the left and the small West Frongoch mine in the centre. Wemyss and the dressing mill sits in the background. By the time this mill was built, Wemyss had been absorbed by Frongoch. They were also known as the Lisburne Mines, after Lord Lisburne, the land owner who lived in Trawscoed.

This scene is still easy to interpret to this day. The road up the valley after Pont Ceunant winds its way underneath the old dressing mill of Wemyss. The dune of waste sand is fenced off, like some grey sand heap, still highly toxic and still polluting the land. This is the waste product of the mill process. Banc Llety Synod looms above and I have also marked the leat that channels water from Frongoch’s machinery, around the Banc to the Wemyss wheels (where David’s hat was rescued in ‘turn of the Wheel’). The water then gets channelled down the valley to be used by the wheels of West Frongoch and Graig Goch.

The mill is built on steps, the higher step being the initial crushing process and each lower step being a part of the separation of the ore. It meant the treated material could be dumped down to the next phase, rather than being carried and lifted up. Gravity is cheaper than manpower.

The gunpowder store is a distance from any part of the operation for safety. They also tended to be circular, to stop any gunpowder dust being lodged in corners. By the 1900’s, the mines used dynamite, which was safer than the black powder.

This is the Frongoch mine, circa 1901, with pitheads and old pumping engines still intact. The tramway was used to send the ore in trucks down by cable below the public road and along to the top of the dressing mill. . To the right and above the pumping engines and mill, the public road runs above the mine. Llyn Frongoch lies to the right of this picture and the road continues to Trisant. In the final book, the mine employs a hundred Italians, who were housed in a barracks to the right and further on from the waterwheel. They form a key part to my story and indeed to Frongoch’s history and its sad end.